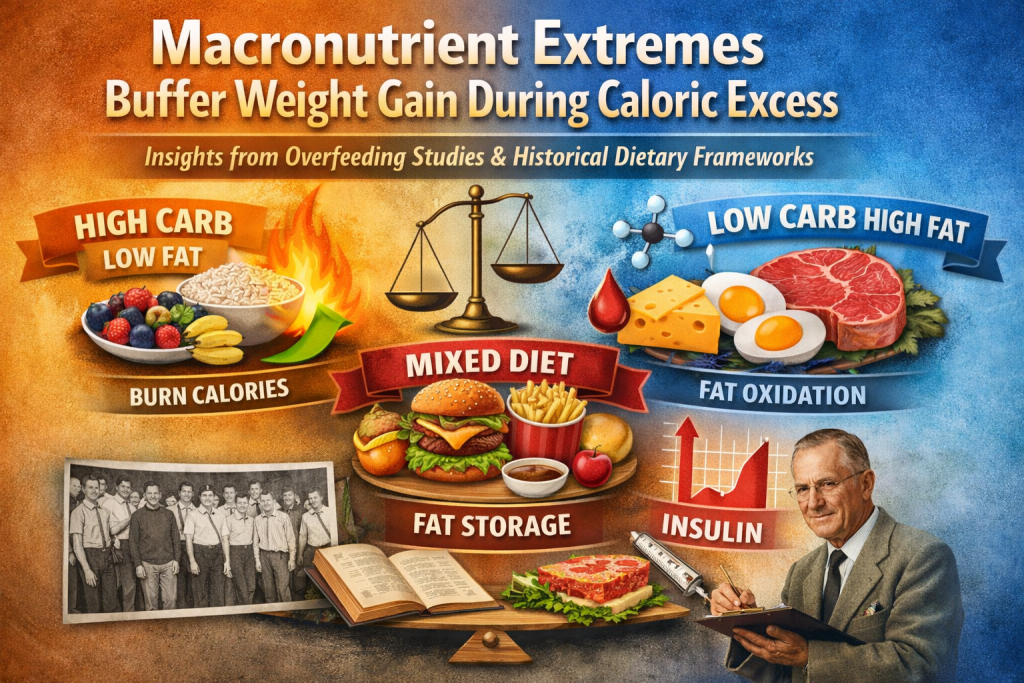

Macronutrient Extremes Buffer Weight Gain During Caloric Excess:

Insights from Overfeeding Studies, Historical Dietary Frameworks, and Personal Observations

Authors: My Random Tips (Conceptualization, Data Curation, Personal Observations); Collaborative Assistance (Methodology, Literature Synthesis).

Independent Researcher, Adelaide, South Australia.

Abstract

Background: Traditional energy balance models predict weight gain from caloric surplus regardless of macronutrient composition. However, emerging evidence suggests that extreme macronutrient profiles—low-fat/high-carbohydrate or high-fat/low-carbohydrate with moderate protein (~20%)—may mitigate gain by enhancing energy expenditure (EE), satiety, and substrate oxidation, while mixed high-fat/high-carbohydrate profiles promote storage via insulin resistance loops.

Objective: This narrative review synthesizes overfeeding studies, historical dietary interventions, anecdotal reports from social media, and food-combining frameworks to explore why caloric excess in macronutrient extremes often results in minimal weight gain, contrasting with mixed-macronutrient overeating.

Methods: We reviewed PubMed-indexed overfeeding trials (n=15, 1980–2025), historical experiments (e.g., Minnesota Starvation Experiment), clinical food plans (e.g., Page Fundamental Diet), and food-combining frameworks (e.g., Hay/Goodheart/Berardi), focusing on body composition, EE, and insulin dynamics during surplus. Anecdotes were sourced via X semantic searches for vegan/high-carb low-fat and carnivore/keto high-fat low-carb excess tolerance. Personal observations of safe zones (low-fat/high-carb or high-fat/low-carb with ~20% protein) vs. danger zone (mixed high-fat/high-carb) informed hypothesis testing.

Results: In extremes, surplus dissipates via adaptive mechanisms: high-carbohydrate/low-fat ramps carbohydrate oxidation and thermogenesis (e.g., 75–85% storage efficiency); high-fat/low-carbohydrate promotes fat oxidation with low insulin (e.g., +1.3 kg vs +7.1 kg in n=1 crossover). Mixed overfeeding yields 90–95% storage efficiency. Protein leverage (untracked but high in extremes) further buffers gain. Historical refeeding (Keys 1944–45) and clinic plans (Page) normalized physiology without mixing, aligning with vegan/carnivore leanness. Social media anecdotes reinforce: Vegans report no gain on high-carb/low-fat excess via satiety; carnivores/keto maintain leanness on high-fat/protein low-carb loads via low insulin/ketosis. Breast milk’s high sugar/fat + low protein promotes infant gain for survival; processed foods mimic this for palatability/gain. Long-term evidence (e.g., constitutional thinness overfeeding) shows resistance persists.

Conclusions: Macronutrient extremes protect against excess-induced gain via partitioning, challenging calories-in-calories-out. Future trials should test proposed safe/danger zones and thresholds (e.g., <88g fat/day on high-carb) in personalized contexts.

Keywords: Overfeeding, macronutrients, weight gain resistance, energy partitioning, food combining, insulin resistance, adipose expandability.

Introduction

Caloric surplus is conventionally expected to drive weight gain proportionally, per the first law of thermodynamics. However, interindividual variability in overfeeding responses suggests macronutrient composition modulates energy partitioning—how surplus calories are oxidized, stored, or expended. Personal patterns show no gain despite months at ~3000 kcal (vs. ~1700 kcal baseline) in low-fat/higher-carb or high-fat/low-carb modes (moderate protein ~20%), but gain when mixing high-fat/high-carb above baseline. This mirrors vegan leanness on high-carb/low-fat and carnivore stability on high-fat/low-carb despite “excess,” vs. mixed diets’ easier storage.

Historical frameworks support: Keys’ Minnesota Starvation Experiment (1944–45) used controlled refeeding to prevent disproportionate gain post-deprivation, emphasizing macro roles. Page’s Fundamental Food Plan normalized blood chemistry in thousands via no refined carbs/mixing (Phase I: low-carb veggies/proteins/fats; Phase II: adds mild carbs/fruits). Food-combining (Hay/Goodheart/Berardi) warns against fat-carb pairing for digestive/insulin efficiency.

This review hypothesizes extremes enable excess tolerance via satiety/EE/oxidation, while mixing traps energy (Randle cycle, insulin loops, ectopic fat if expandability limited).

Group photo of the participants in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment (1944-1945). Source: Wikipedia / Wikimedia Commons.

Keys’ recruitment brochure cover: “Will you starve that they be better fed?” Source: NCBI/PMC (Figure image hosted by NIH).

Proposed Framework for Macronutrient Partitioning

From personal testing and Page’s no-mixing/refined-carb avoidance:

- Safe Zone Metabolically: Higher Carb + Lower Fat + Moderate Protein (~20%) — GM (Glucose Meal Low Fat)/GS (Glucose Snack), e.g., steamed potatoes + lean fish.

- Safe Zone Metabolically: Higher Fat + Lower Carbs + Moderate Protein (~20%) — FM (Fat Meal Low Carb)/FS (Fat Snack), e.g., steak + butter/cabbage.

- Danger Zone: Higher Fat + High Carb + Moderate Protein (~20%) — mixed excess drives fat gain; limited expandability → ectopic fat (liver/muscle), elevated basal glucose, insulin resistance loop (insulin ramps ineffectively).

- LM (Veg + Lean Meat) supports neutrally.

This avoids Page’s “poor” combos and aligns with Keys’ macro control for recovery without excess gain.

Diagram version of Dr. Melvin Page’s Phase I vegetable “carb band” idea (for reliable display in browsers). Original PDF source: IFNH.org Page-Food-Plan.pdf

Cover-style placeholder graphic (so the page loads reliably). If you want the original document, link to: Scribd document page

Evolutionary and Developmental Perspectives: Breast Milk Composition and Processed Foods

Breast milk’s macro composition (~7% carbs/lactose, 3.8% fat, 1% protein; 65–70 kcal/100mL) naturally promotes rapid infant weight gain for survival, providing high energy from sugar/fat for brain/growth reserves against famine. This mixed high sugar/fat + low protein is evolutionary for fat storage from birth, as in Keys’ starvation subjects needing controlled refeed to regain without issues.

Commercial processed foods mimic this (high sugar + high fat + low protein) for hyper-palatability, driving overeating/gain (e.g., +500 cal/day on UPF diet, +2lbs). UPFs exploit scarcity wiring in abundance, leading to obesity. This reinforces the danger zone—mixed macros trap fat naturally/evolutionarily, but extremes avoid it.

References

- Keys A. The Great Starvation Experiment, 1944-1945. Project File: 2005-Mad-Science-Museum-Ancel-Keys-Starvation.pdf.

- Page ME. Phase I and II Food Plan. Project Files: 26756497-Phase-I-and-II-Food-Plan-Dr-Melvin-Page.pdf; The-Page-Fundamental-Food-Plan-Food-Combining-Apendix-from-Lab-Desk-Ref.pdf.

- Kim SY, et al. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2020;63(8):297-303. (Breast milk macros).

- Prentice P, et al. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105(6):641-9. (HM %carb + gain).

- Hall KD, et al. Cell Metab. 2019;30(1):67-77.e3. (UPF +500 cal/gain).